- Error

- Global Economy

- Econlib

- Error

RSS Error: A feed could not be found at `http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/feed/`. This does not appear to be a valid RSS or Atom feed.

In the early 20th century, America was buzzing with Progressive Era reforms aimed at taming the excesses of industrialization. One landmark was the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906, hailed as a victory for consumer safety. It banned poisonous ingredients in food and drink, required accurate labeling, and cracked down on imitations. But when it came to whiskey, was it truly about protecting the public from deadly adulterants? Or was it a classic case of dirty politics, where special interests use government power to disadvantage competitors?

Economists have long debated the origins of regulation through two lenses: public interest theory and public choice theory. Public interest theory sees regulation as a noble response to market failures like asymmetric information, where consumers don’t have the expertise to spot hidden dangers. Public choice theory, pioneered by scholars like James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock, flips the script: regulations often emerge from rent seeking, where powerful industry groups lobby for rules that boost their profits at the expense of consumers and competitors. Oftentimes, rent seeking is most successful when there is at least a semblance of a public interest concern to bolster the argument for regulation among those hoping to shape it.

In my recent paper in Public Choice, coauthored with Macy Scheck, “Examining the Public Interest Rationale for Regulating Whiskey with the Pure Food and Drugs Act,” we explore a case in which the historical evidence leans heavily toward the explanation offered by public choice theory. Straight whiskey distillers, who age their spirits in barrels for flavor, pushed for regulations targeting “rectifiers,” who flavored neutral spirits to mimic aged whiskey more cheaply. The rectifiers were accused of lacing their products with poisons like arsenic, strychnine, and wood alcohol. If true, the regulation was a lifesaver. But was it?

Whiskey consumption boomed in the decades before 1906, without federal oversight. Sales of rectified whiskey were estimated at 50–90% of the market. From 1886 to 1913, U.S. spirit consumption (mostly whiskey) rose steadily, dipping only during the 1893–1897 depression. If rectifiers were routinely poisoning customers, you’d expect markets to collapse as word spread, an example of Akerlof’s “market for lemons” in action. No such collapse occurred.

Chemical tests from the era tell a similar story. A comprehensive search of historical newspapers uncovered 25 tests of whiskey samples between 1850 and 1906. Poisons turned up infrequently. Some alarming results came from dubious sources, like temperance activists. One chemist, Hiram Cox, a prohibitionist lecturer, claimed to find strychnine and arsenic galore—but contemporaries debunked his methods as sloppy and biased.

Trade books for rectifiers, which contained recipes, reveal even less malice. These manuals, aimed at professionals blending spirits, rarely list poisons. When poisons did appear, their use was in accordance with the scientific and medical knowledge of the time. Many recipe authors explicitly avoided known toxins, noting it was more profitable to keep customers alive and coming back.

We examined home recipe books for medicine and food. We found that the handful of dangerous substances that were included in whiskey recipes were often recommended in home medical recipes for everything from toothaches to blood disorders. This suggests people, including regulators, did not know of their danger at that time.

Strychnine was found in niche underground markets where a small number of thrill-seekers demanded its amphetamine-like buzz, or in prohibition states where bootleggers had no viable alternatives. But rectifiers avoided it; it was expensive and bitter.

What about reported deaths and poisonings? That is our final piece of evidence. Newspapers of the day loved sensational stories such as murders or suicides. Yet a keyword search for whiskey-linked fatalities from 1850–1906 yielded slim pickings outside of intentional acts or bootleg mishaps. Wood alcohol, which was listed in no recipes, caused the most issues, but often in isolated cases, like a 1900 New York saloon debacle where 22 died from a mislabeling.

Overall, adulterated whiskey was hardly a serious safety concern.

Harvey Wiley, the USDA chemist who championed the Pure Food and Drugs Act, admitted under questioning that rectified ingredients weren’t inherently harmful—they just weren’t “natural.” His real motive? Rectified whiskey was a cheap competitor to straight stuff. Wiley’s correspondence, unearthed by historians Jack High and Clayton Coppin, shows straight distillers lobbying hard and framing regulation as a moral crusade while eyeing market share. President Taft’s 1909 compromise allowed “blended whiskey” labels but reserved “straight” for the premium, aged variety— a win for the incumbents.

The lesson? Regulations are rarely the product of pure altruism. As Bruce Yandle’s “Bootleggers and Baptists” model explains, moralists (temperance advocates decrying poison) team up with profiteers (straight distillers seeking barriers to entry) to pass laws that sound virtuous but serve narrow interests. The Pure Food and Drugs Act may have curbed some real abuses elsewhere, but for whiskey, it was more about protecting producers than consumers. Cheers to that? Not quite.

Daniel J. Smith is the Director of the Political Economy Research Institute and Professor of Economics at the Jones College of Business at Middle Tennessee State University. Dan is the North American Co-Editor of The Review of Austrian Economics and the Senior Fellow for Fiscal and Regulatory Policy at the Beacon Center of Tennessee.

(0 COMMENTS)Russ buys 5 sirloins per week. True or false: If the price of sirloin rises by $5 apiece, and if Russ’ preferences and income remain constant, he will have $25 a week less to spend on other things.

Solution:One of the first things I emphasize in my micro principles course is that the behavioral patterns we observe in the real world are shaped by prices. When prices change, so does behavior.

This idea comes straight from consumer theory. In standard models, people maximize utility by consuming each good up to the point where the marginal value of one more unit equals its market price. When the price of a good rises—as in the example we’re considering here—the marginal value at the optimum must also rise. In this case, the marginal value at the new optimum must be $5 higher to match the new price of sirloin.

Because marginal value falls as Russ consumes more sirloin, he can restore the equality between marginal value and price—the condition for his optimum—only by consuming less. Without more information about his income or preferences, we can’t say exactly how much less, but we do know that he will buy fewer sirloins than before.

Thus, the statement in the original question is false: Russ will reduce his consumption of sirloin when its price rises, so it doesn’t necessarily follow that he has $25 less to spend on other things.Once More, With Math

We can also see this result by examining Russ’s budget constraint. Suppose Russ uses his income, M, to purchase sirloin, S, and a composite good we’ll call “all other goods,” Y. His budget constraint is therefore

M=PSS+PYY

Here, PS and PY denote the price of sirloin and the price of all other goods, respectively.

The question tells us that the price of sirloin rises by $5, so his new budget constraint is

M=(PS+5)S+PYY

Since Russ’s income, M, and the price of other goods, PY, remain constant, the maximum amount of “all other goods” he could buy if he purchased no sirloin remains the same at M/PY. In that sense, the maximum quantity of all other goods he can consume hasn’t changed.

However, the slope of his budget line has changed: sirloin has become relatively more expensive, so the budget line pivots inward around that intercept. This change in relative prices reduces Russ’s feasible combinations of sirloin and other goods, prompting him to move to a new optimum with less sirloin and more of other goods.

In this sense, Russ’s real income has fallen even though his nominal income remains the same. But because he reoptimizes—reallocating his spending between sirloin and other goods when the price changes—it does not follow that he has $25 less each week to spend on other goods.

(8 COMMENTS)The usual case for free trade is not the best case for free trade. The usual case is based on static efficiency, meaning making better use of a fixed set of resources. Economists use the term comparative advantage to describe how, if humans choose to specialize and trade with one another, each can end up better off than if they produce everything for themselves.

But trade has an even more important role to play in what economists have come to call dynamic efficiency, which is the ability of an economy to exploit innovation and increase living standards over time. This dynamic efficiency is a central concern of the economists who shared the 2025 Nobel Prize: Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt, and Joel Mokyr.

Aghion and Howitt explored the process that Joseph Schumpeter famously labeled creative destruction. One hundred years after Schumpeter, we see that process all the time in the realm of computers, communications technology, and software. Mainframe computers were displaced by personal computers and the Internet, landline phones were displaced by smartphones and cellular communication, and artificial intelligence now threatens to upend many industries.

Mokyr was recognized for his study of economic history, particularly the Industrial Revolution. He pointed out that technology improves through a virtuous cycle in which practical inventions inspire curiosity, leading to scientific discovery, enabling improvements to practical inventions.

Mokyr also emphasized how the process of innovation and growth can be stifled by protectionism. It is dynamic efficiency that is stymied when barriers to trade are erected. That is an important lesson that today’s policy makers seem reluctant to learn.

For our 2011 book, Invisible Wealth,2 Nick Schulz and I were fortunate to be able to include an interview by Nick with Mokyr, as well as interviews with other proponents of dynamic efficiency, including Douglass North, Robert Fogel, and Paul Romer. Given his recent recognition with the Nobel Prize, the themes from that interview are worth revisiting.

Mokyr argues that the Enlightenment included a rebellion against economic protectionism.

I argue in my book that one of the things that happens in eighteenth-century Europe is a reaction against what we today would call, in economic jargon, “rent-seeking,” and that this, to a great extent, is what the Enlightenment was all about…It was about freedom of religion, tolerance, human rights—it was about all of those things. But it was also a reaction against mercantilism…

Adam Smith isn’t, you know, as original as people sometimes give him credit for…All these people were saying essentially the same thing: we need to get rid of guilds, monopolies, all kinds of restricted regulatory legislation. And above all, you need free trade, both internal—which Britain had but the Continent did not—and international….

…when you look at the few places in Europe where the Enlightenment either didn’t penetrate or was fought back by existing interests, those are exactly the countries that failed economically. You think of Spain and Russia, above all. (p. 119–120)

Mokyr argued that ideas spread through the circulation of people.

Much of the communication about technology is in fact through personal transmission…You can only learn so much from books, even now. (p. 122)

Tacit knowledge is acquired in person.

Mokyr warned that protectionist interests always lurk within a prosperous society.

Looking back at the record, it is quite clear that nobody has held technological leadership for a very long time. The reason for that is primarily that technology creates vested interests, and these vested interests have a stake in trying to stop new technologies from kicking them out in the same way that they kicked out the previous generation…And they have all kinds of mechanisms. One is regulation, in the name of safety or in the name of the environment or in the name of protection of jobs. They will try to fend off the new to protect the human and physical capital embedded in the old technology. (p. 123)Without the pressure of international trade, an industry can stagnate.

Let’s look at the American automobile industry in the 1950s. Absolutely zero technological change…in the late 1960s they were still making things like the Vega and the Pinto, which were the worst cars ever made…

But then something happened: the Japanese showed up…the Japanese made better cars from better materials. They made them cheaper. The cars lasted longer. And guess what? Today’s American cars are far, far better than they were in the late 1950s to early 1970s—not because Americans couldn’t have done it earlier, but because openness forced them to do it. (p. 126)

Today in America, many politicians are listening to the siren song of the restrictionists. Industrial policy, which means protectionism, is popular. Globalization and neoliberalism are bad words.

But if the past is any guide, anti-globalization is going to degenerate into crude special-interest politics. Instead of dynamic efficiency, we will end up with economic stagnation. The 2025 Nobel Laureates can remind us of that.

[1] Quoted from an interview in Arnold Kling and Nick Schulz, Invisible Wealth, p. 119.

[2] Invisible Wealth was originally published in 2009 as From Poverty to Prosperity

The conclusions we reach about the world are, to a large extent, influenced by our underlying intuitions. Various writers have discussed how our immediate sense of how the world works has a huge influence on how our worldviews develop.

Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions posits that there are fundamentally different “visions” about the world that drive the differing worldviews we see. Following Joseph Schumpeter, Sowell defined a vision as a “pre-analytical cognitive act”—a sense of how things are prior to deliberate consideration. People who naturally hold what he called the constrained vision (or, in later works, the tragic vision) have very different reactions to the world from those who hold what he called the unconstrained vision (or the utopian vision).

Knowing someone’s intuitive framework could explain a lot about how they evaluate different questions of public policy. One’s initial reaction to hearing about “click-to-cancel” regulation seems like a useful way to gauge overall instincts regarding regulation.

Some businesses make it very easy to sign up for services, and very time-consuming to stop paying. The easiest example is fitness centers. I once had a membership at a gym where you could sign up for a membership online in about thirty seconds, without ever setting foot in the facility. But canceling a membership required first a notification through the website or app, then coming in person to the facility with a handwritten statement declaring your desire to end your membership, and then your membership would be canceled after the end of the next billing cycle.

I’ve seen some people speculate that this is how Planet Fitness stays in business while only charging $10 a month for a membership. They make it easy for people to join in a moment of inspiration (I’m sure New Year’s resolutions cause a jump in membership), and they make it a hassle to close your membership. Because the membership is so inexpensive, it’s also easy to overlook. People can go years before they finally jump through the hoops to cancel an unused membership.

The click-to-cancel rule would prohibit these arrangements. Under such a regulation, if the business provides a way to join with low transaction costs, they must provide a way to cancel with equally low transaction costs.

Here are three reactions people might have after hearing about this regulation:

I’ll call the first reaction a classical welfare economics perspective. To the textbook welfare economist, economic policy should improve economic outcomes by streamlining and optimizing economic arrangements. Negative externalities should be taxed. Positive externalities should be subsidized. Transaction costs should be minimized because they often prevent efficient outcomes. These kinds of contracts, it is argued, create unnecessary transaction costs. Therefore, a click-to-cancel rule would have the effect of lowering transaction costs, which in turn will tend to bring about more efficient outcomes. Thus, this regulation would be welfare-enhancing. Seems like a good idea. But it’s not so simple.

Martin Gurri expressed concern with this optimization mindset in his book The Revolt of the Public:

Our species tends to think in terms of narrowly defined problems, and usually pays little attention to the most important feature of those problems: the wider context in which they are embedded. When we think we are solving the problem, we are in fact disrupting the context. Most consequences will then be unintended.

The second reaction is more cautious. It is inspired by the type of thinking often associated with Hayekian economics, but is also in the work of economists like Vernon Smith. This mindset sees the economy not as an optimization problem but as an unfathomably complex ecosystem. We can know general conditions that allow the ecosystem to grow and thrive, like property rights and freedom of contract. But attempting a targeted intervention to bring about a specific result is a bit like trying to eliminate a pest from an ecosystem by introducing a new predator. You’re not simply adjusting a static variable with no further effects. You’re interacting with an adaptive ecosystem.

The Hayekian perspective encourages those who share it to point out that there’s always been an option for gyms to compete against other gyms by making it easy to cancel a membership. If customers want it and entrepreneurs could provide it, but that arrangement isn’t offered, it reveals something. We can interpret this as a sign that this seemingly obvious problem-and-solution combination isn’t as simple as it appears. Here’s where the caution comes in: If things are more complicated, tread lightly.

The third reaction is a harder-libertarian take based on freedom of association and the associated freedom of contract. This reaction is one against interfering with a private agreement. As long as the terms for signing up and leaving are clearly stated in the contract without fraud, and people willingly sign, then that is that. Whether or not it would be welfare-enhancing to forbid these arrangements is beside the point. Nobody has any right to try to force a change in the terms of that contract, or to tell people they can’t draw up and sign such contracts if they so choose. End of story.

Which of these reactions, dear reader, most closely describes your initial impulse regarding the click-to-cancel rule?

As an Amazon Associate, Econlib earns from qualifying purchases. (4 COMMENTS)

Today, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Joel Mokyr (Northwestern University), Philippe Aghion (London School of Economics), and Peter Howitt (Brown University) “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.”1 This follows a recent trend for the Committee to award to economics focused on economic growth, following Acemoglou, Johnson, and Robinson in 2024 and Kremer, Duflo, and Banerjee in 2019. Time and space prevent me from providing a detailed discussion of the ideas behind each prize, but they are all crucial to our understanding of economics.

One of the big mysteries of human history is the so-called “hockey-stick of prosperity.” That is, the fact that, for much of human history, standards of living were virtually unchanged. Very little separated the Roman citizen in 1AD from the British citizen in 1700. But, starting in the 1700s, standards of living skyrocketed.

From 1AD to 1700AD, few changes happened: sails and animal-powered transport dominated, medical science hadn’t advanced much, and machinery was unknown. From 1700 to 1800, changes were beginning: mechanical engines were introduced and the Industrial Revolution began. Between 1800 to 1900, the world went from horse and buggy to steam engines. Between 1900 and 1960, humanity went from automobiles to planes to landing on the moon.2 Diseases were eradicated, lives were improved. Real poverty fell from around 90% of the global population to less than 10%. Nothing like this had happened before, and it kept happening. Even the most optimistic economists at the time had trouble explaining it.

Enter Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt. Collectively, their work helped explain why this growth happened, why it happened where it did, and how it is sustainable.

Mokyr argues that the Industrial Revolution and the benefits it provided were no accident of history, but rather the result of institutions. Economic growth arises out of two kinds of knowledge: propositional knowledge (how and why things work) and prescriptive knowledge (practical knowledge of necessary things to get things to work, such as institutions or recipes). These two forms of knowledge work together, building on one another, to create economic growth. For example, economic sciences (propositional knowledge) will tell us where prices come from, how people coordinate their behavior, etc. That understanding, in turn, helps us consider what kind of institutions (prescriptive knowledge) are needed to foster those trends.

Furthermore, the fragmented state of Europe led to the rise of the Industrial Revolution. With various states competing with each other for political dominance, and none particularly large, people could move (or flee) if their ideas were being suppressed. In large unitary nations like China and India (which were of roughly the same technological level as Europe pre-industrialization), ideas were suppressed and people had little option to leave. Because it subverted the suppression of new ideas, the fragmentation of Europe led to greater technological strengths. This trend could sometimes even be observed within states, such as in the British Empire. Scotland was a backwater, mostly ignored by the ruling elite in London post-unification, and yet that is where the Industrial Revolution kicked off.

Mokyr called this the culture of growth (also the name of his excellent 2016 book). Technological innovation is not random, but rather requires a culture that promotes innovation and a market for ideas.

Aghion and Howitt contribute in a different way. Their landmark paper “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction” (Econometrica, 60(2)) builds a mathematical model of Joseph Schumpeter’s verbal model of creative destruction. Firms face both a carrot and a stick to innovate. The carrot is the rents they can get for innovations. Through the creative process, they make old technologies obsolete, both eliminating the old technologies and grabbing market share (or rents). The stick comes from the constant threat of others acting the same way: each must innovate to prevent losing rents.

But Aghion and Howitt also uncovered limitations. When the rents become very large, an incumbent firm can create barriers to entry. This reduces the stick from competition. Further, once rents (the carrot) have been secured, there is less incentive for firms to innovate. Differences in firm, market, and legal structures help explain why some industries are highly innovative and others are stagnant.

All three winners explain economic growth through technology and culture (broadly defined). My little overview does not pretend to present the entirety of their work. I highly recommend the Nobel Committee’s overview of their contributions.

Congratulations to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for a well-deserved award!

[1] Please, nobody say “There is no Nobel Prize in Economics. It’s the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.” We all know.

[2] As an aside, I find the whole space program amazing. A bunch of scientists went to folks like Chuck Yeager and said, “We have an idea: we’re going to take missiles, remove the warhead, bolt on a couple of seats, and fling you at the Moon,” and these pilots said, “Sounds fun! Sign me up.”

As an Amazon Associate, Econlib earns from qualifying purchases.

(18 COMMENTS)

What drives the seeming relentless dynamism of Tokyo? Is there something special about Japanese culture? Joe McReynolds, co-author of Emergent Tokyo, argues that the secret to Tokyo’s energy and attractiveness as a place to live and visit comes from policies that allow Tokyo to emerge from the bottom up. Post-war black markets evolved into today’s yokocho–dense clusters of micro-venues that turn over, specialize, and innovate nightly–while vertical zakkyo buildings stack dozens of tiny bars, eateries, and shops floor by floor, pulling street life upward. The engine? Friction-light rules: permissive mixed-use zoning, minimal licensing, and no minimum unit sizes let entrepreneurs launch fast and pivot faster. And surrounding this emergent urban landscape there’s plenty of new housing with excellent transportation infrastructure to let ever-more people enjoy Tokyo’s magic.

What drives the seeming relentless dynamism of Tokyo? Is there something special about Japanese culture? Joe McReynolds, co-author of Emergent Tokyo, argues that the secret to Tokyo’s energy and attractiveness as a place to live and visit comes from policies that allow Tokyo to emerge from the bottom up. Post-war black markets evolved into today’s yokocho–dense clusters of micro-venues that turn over, specialize, and innovate nightly–while vertical zakkyo buildings stack dozens of tiny bars, eateries, and shops floor by floor, pulling street life upward. The engine? Friction-light rules: permissive mixed-use zoning, minimal licensing, and no minimum unit sizes let entrepreneurs launch fast and pivot faster. And surrounding this emergent urban landscape there’s plenty of new housing with excellent transportation infrastructure to let ever-more people enjoy Tokyo’s magic.

It’s morning in Tokyo. You’re sitting on your balcony with a cup of coffee or tea, enjoying the rising sun over the bay. Birds chirp. All is peaceful—until that peace is shattered by a giant radioactive kaiju named Godzilla.

You watch in horror as the massive, irradiated monster makes landfall and begins his rampage through the city, crushing buildings and leaving devastation in his wake. As the chaos unfolds, a surreal thought floats through your mind: Well, at least Tokyo’s construction companies will be busy. There’s got to be some good in all this, right?

Frédéric Bastiat would like a word with you.

Bastiat was a 19th-century French economist, statesman, and author. One of his most influential works is the essay “What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen” (published in Economic Sophisms), where he outlines what later became known as the broken window fallacy. Bastiat argues that economic analysis often focuses on what is immediately visible—“what is seen”—while ignoring opportunity costs and longer-term consequences—“what is not seen.”

In his famous example, a man named Mr. Goodfellow and his son pass by a shop. The boy breaks the shop’s window, prompting the shopkeeper to pay a glazier to fix it. Goodfellow suggests this is good for the economy, as it gives the glazier work. But Bastiat challenges this view: yes, the glazier earns a wage—but the shopkeeper has lost the ability to spend that money elsewhere, such as on new shoes or investment in his business. The economy hasn’t grown; it has merely shifted activity from one area to another, while real wealth has been destroyed.

Now extend Mr. Goodfellow’s logic: if breaking a window stimulates the economy, why not burn down an entire city to create construction jobs?

Enter our old, loveable kaiju, Godzilla.

As Godzilla rampages through Tokyo—destroying homes, offices, stores, and factories—Bastiat would be shaking his head at any claim that Japan’s construction industry, and the nation as a whole, stands to benefit. The destruction may generate activity, but it’s not productive activity. The rebuilding process doesn’t enhance the nation’s wealth—it merely attempts to restore what was lost.

The cost would be astronomical: not just in yen, but in lives. Thousands would perish, and countless more would suffer injuries. Critical infrastructure would be destroyed. Nuclear contamination from Godzilla’s radioactive presence would spread across the city, requiring massive environmental cleanup and public health interventions. Defense spending would skyrocket as Japan (and perhaps other nations) prepare for future kaiju attacks. All of this would be “seen”: construction contracts awarded, cleanup crews deployed, emergency services expanded.

But Bastiat would point us to what is not seen: the foregone alternatives. The taxpayer money spent on reconstruction could have been used for infrastructure upgrades, education, scientific research, or tax relief. The human capital lost in the destruction cannot simply be rebuilt. Trade would suffer too, as foreign firms reconsider partnerships with a nation subject to unpredictable monster attacks. Global allies might offer aid—a noble gesture, but one that, again, diverts resources to damage control rather than wealth creation.

In short, the Godzilla problem is not an economic opportunity—it’s a profound economic loss. The fallacy lies in mistaking frenetic (re)building for real growth. This kind of thinking persists today, whenever disaster spending is misread as economic stimulus. Just because money is being spent doesn’t mean wealth is being created.

Even as Mr. Goodfellow’s naïve optimism echoes through time, Bastiat’s insights remind us to look deeper. And even a giant radioactive kaiju isn’t immune to the economic truths Bastiat laid out nearly two centuries ago.

Ethan Kelley is a Legislative Analyst for the Knee Regulatory Research Center at West Virginia University.

(5 COMMENTS)

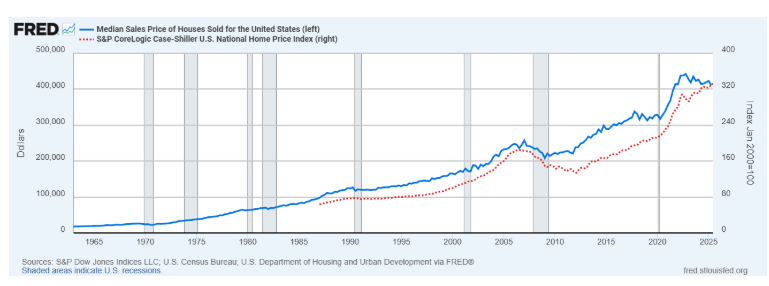

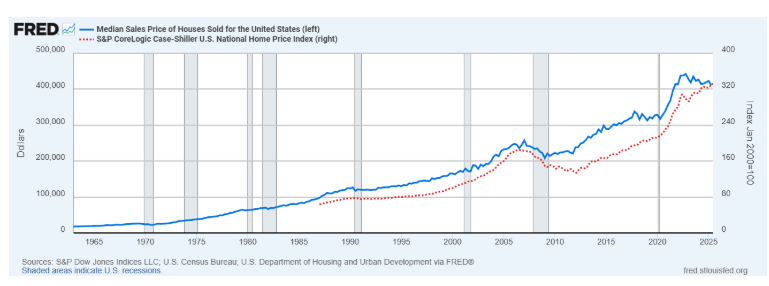

Average home prices remain very close to the all-time highs reached at the beginning of the year. Accordingly, public opinion surveys show rising concern about the issue of housing affordability, and politicians are taking notice. The Trump administration has waded in with a potentially forthcoming national housing emergency declaration so the President can do… something. We may have to wait until a decree is issued to see what exactly Mr. Trump thinks his emergency powers are in the realm of housing policy.

But are houses really more expensive over the long run, or is it just an economic mirage? As an economist with a background in residential construction, I think about this issue often.

When I read articles about the housing affordability crisis, I tend to agree with the economically-informed consensus that America has a fundamental housing supply problem. A combination of regulatory constraints—zoning, permitting, energy-efficiency standards, occupational licensing, etc.—raises home construction costs. Tariffs and the purge of illegal immigrant labor are not helping, either. I endorse the argument that regulatory easing would make housing significantly more affordable.

On the other hand, I sense that much of the fuss about ever-rising home prices is based on incomplete analysis. It does not account for enough of the relevant factors to provide a satisfactory explanation of the observed trends in the data. Good economic analysis must hold other factors constant—the famous ceteris paribus assumption. When it comes to home price analysis, there’s a raft of other factors to consider. Some fairly simple calculations with easily available data support an argument that home prices are not significantly higher than their long-run average.

The Other Factors that Matter in HousingSo what are the ceteris we must hold paribus when analyzing long-run trends in US home prices? Let’s start with the big, obvious one: inflation. We can’t compare nominal home prices from 2019 to 2025 (CPI grew 26% over these six years alone), much less from 1990 or 1960 or whatever date one selects as the golden age of affordability.

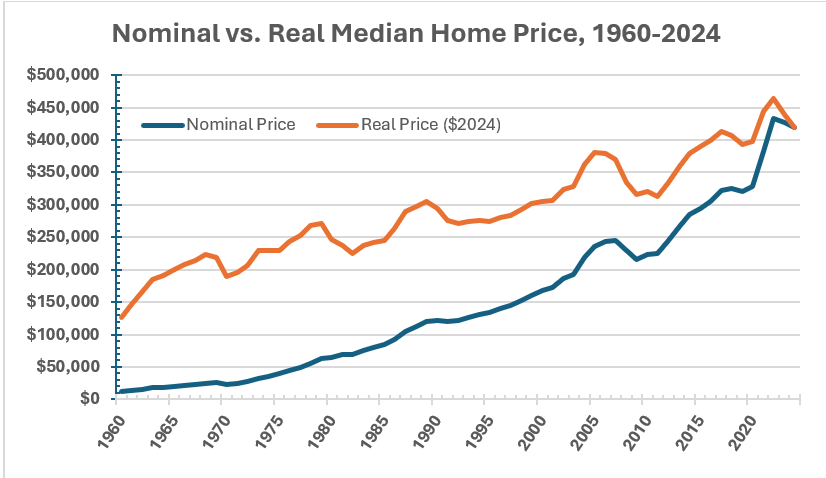

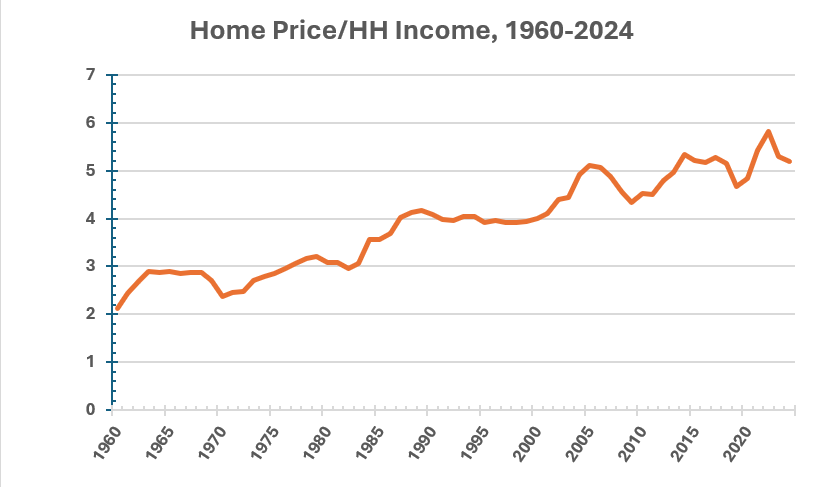

Let 1960 (the earliest year for which I can obtain data points for all of my ceteris paribus categories) represent the paragon of home affordability in the US. While the nominal median home price rose by 3,421% from 1960 to 2024, adjusting this for inflation using the Consumer Price Index shows a more modest but perhaps still distressing rise of 232%. But let’s now also factor in much smaller, but significant, growth in household incomes over this time frame. The typical practice is to divide the median home price by the median household income to get the home price/ household income ratio. In real terms, this ratio rose from about 2.1 to about 5.2, or 145%, over the same time frame.

Next, let’s consider what, exactly, people are getting with their purchase of the median home. In 1960, the median home built in the US was 1,500 square feet. Median home size rose steadily, peaking at about 2,700 square feet in the mid-2010s before declining slightly to 2,400 square feet in 2024. Assuming bigger is better and that people are happy to shell out more money for more house, we can adjust for this size factor by calculating real home price per square foot of home size. This metric increased by 107% from 1960 to 2024. Still a large increase, but far more manageable than that raw real median price by itself or adjusted merely for household incomes.

We’re getting closer, but I want this to be a comprehensive adjustment. One very important analytical factor I learned from the great Thomas Sowell is to be on the lookout for composition effects, or changes in the characteristics of groups over time that can skew simplistic statistical snapshots. Sowell teaches us to be on the lookout for composition effects in any household statistic, because household size can and does change significantly over time. In 1960, the average US household was 3.33 people. This figure dropped to about 2.5 by the 2020s, with most of that decline taking place before the 1990s.

This means that the median household income is divided amongst a smaller number of household members, understating the growth of household income over time on a personal level. In other words, real median household income per person went up by more than is apparent in the overall household income data series. We can factor this into our home price analysis by calculating the ratio of real home price to real household income per person. This metric rose by 96% over the 1960–2024 period.

Finally, let’s combine the change in home size along with the change in household composition in that last calculation. Our final adjustment results in the ratio of real home price per square foot to real household income per person. Drumroll, please: by this comprehensively adjusted metric, housing affordability rose by a paltry 6% from 1960 to 2024, and is actually down substantially from its peak in the late 1970s.

Moreover, all of these adjustments do not account for perhaps the most important change: that of home quality in terms of features and amenities that have become more common over the years. I have yet to find an index of home quality that tracks these attributes in a reliable way. I do have a strong impression, based on personal experience and tidbits of data, from which I arrive at a confident conclusion that today’s homes are nicer places to live than those of 30 or 60 years ago. As a 2011 US Census report summarizes, in addition to larger home sizes, “homes built today have almost more of everything—different types of rooms such as more bedrooms and bathrooms, more amenities such as washers and dryers, garbage disposals and fireplaces, and more safety features, such as smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and sprinkler systems.” Today’s bigger, roomier homes also have more energy-efficient utilities, more user-friendly appliances, more garage space, bigger and more well-appointed kitchens where stone countertops replaced Formica, and so on. If we could find a way to factor in all of these changes to the comprehensive home price adjustment, it might show zero change or even a fall in home prices, ceteris paribus.

In conclusion, the housing affordability crisis is a nothingburger!

While it’s important to think carefully about the changes in the ceteris, I want to reiterate that there is a housing price problem, and it deserves attention and a smart public policy response. I hope my “comprehensive” real home price adjustments here are thought-provoking, but this analysis is lacking in at least two major ways: 1. It cherry picks the start and end points; 2. It’s national aggregate data, so it does not pick up regional variations in home price changes over time.

If you look at ten-year spans, there’s a lot of fluctuation in home price shifts, even by my preferred ratio of real home price per square foot to real household income per person metric. 2024 prices were 22% higher than 10 years prior, giving the up-and-coming generation ample grounds to complain that home prices are getting out of reach. The recent spurt of home appreciation also validates the complaint that housing markets serve to transfer wealth from poorer millennials to well-off boomers. Housing price growth also varies greatly by region. Hot markets—mostly coastal and sunbelt metros—saw 10-year price growth at 1.5 to 2 times larger than the national average. Cooler markets in parts of the south and Midwest saw growth rates not much higher than overall CPI inflation.

As this excellent map from Visual Capitalist shows, it is much easier to afford a house (ceteris paribus, of course!) in the Midwest than in the West, Northeast, or Florida. (I knew there had to be a compensating differential for our miserable Michigan winters!)

Getting a handle on escalating home prices is a simple, but not politically easy, fix. We need to claw back the relative growth in home construction costs. In other words, we need the housing supply curve to “shift to the right” more than the demand curve has shifted. Builders know exactly what this would take: less restrictive zoning (especially for multifamily units), easier licensing and permitting processes, less stringent building codes and energy standards, freer markets in labor and materials, and maybe a consumer acceptance of smaller, simpler homes.

All data sourced from Federal Reserve Economic Data: fred.stlouisfed.org.

Dataset and calculations available upon request: tylerwatts53@gmail.com

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics at Ferris State University.

(10 COMMENTS)Recently, the Trump Administration announced that H-1B applications would face a new $100,000 fee (in addition to the already existing fees, not to mention legal fees). The H-1B visa allows firms to hire foreign individuals with a college degree for their positions. Firms enter a lottery, and if they win the lottery, they can hire a foreign professional. The H-1B can eventually be converted into a green card. Since universities are exempt from the lottery, it is a way for foreign students to try to stay in the US after their degree. Much of this policy change is up in the air, so this post isn’t about the change per se, but rather the change prompted some thoughts.

The Trump administration argues that this fee is necessary to prevent American firms from hiring foreign workers cheaply, at the expense of American workers. Given the way it is structured, it is unlikely the H-1B visa has that effect. But, for the sake of this post, we’ll take the argument as given.

Will the fee lead to more hiring of American workers? It’s tempting to think so. After all, if the price of foreign workers rises, then fewer foreign workers will be hired. That is just the law of demand at work: as price goes up, quantity demanded goes down.

But there is an implicit assumption in the Trump administration’s argument: that domestic workers are the next-best option for firms compared to foreign workers. That is not necessarily the case. The law of demand tells us that firms will adjust their hiring, but it does not tell us along what margins firms will adjust. Perhaps they will fill their roles with American workers; after all, the cost of domestic workers is now relatively lower compared to foreign workers. But the firm could also opt to change its operations, or even relocate outside the country.

The law of demand tells us that as the price of something goes up, quantity demanded falls (all else held equal). Economic theory tells us that as relative prices change, people will adjust their behavior. But theory does not, indeed, it cannot tell us how they will adjust. That will depend on the relevant alternatives they face at the juncture of choice. What the relevant alternatives are depends on the particular circumstances of time and place they find themselves in and the goals of firms and individuals.

(13 COMMENTS)On September 26, the British prime minister’s office announced that

“A new digital ID scheme will help combat illegal working while making it easier for the vast majority of people to use vital government services. Digital ID will be mandatory for Right to Work checks.”

I was getting ready to offer an argument against government ID papers when I realized that I had already done so in an EconLog post of more than five years ago: “The Danger of Government-Issued Photo ID” (January 8, 2019). I think my arguments are still valid, and I recommend this previous post. But I would like to emphasize a few points, especially in light of the British government’s push.

Digital ID is even more dangerous than photo ID, precisely because it further diminishes the cost of tyranny for the government. What about, as in China, attaching social-credit points to digital IDs to reward obedient citizens? There is always another good reason for Leviathan to increase its power and to make citizens believe that granting it is in their own individual interests.

Some readers may question my mention of Leviathan. But I ask them to reflect on how the general power of the state has, despite the correction of injustices against some minorities, grown to the point where it seems nobody can stop it. The fact that more and more people support it for different reasons makes its growth more dangerous, not less.

The British government only abolished the wartime national ID card seven years after the end of WWII, and only after a citizen resisted. In 1950, Clarence Henry Willcock, stopped by a policeman as he was driving, refused to show his ID card. “I am a Liberal and I am against this sort of thing,” he said. He lost twice in court, but the movement against ID cards he started persuaded the government to abolish them in 1951. (See Mark Pack, “Forgotten Liberal Heroes: Clarence Henry Wilcock.”)

One justification for official ID papers is that it assists citizens in doing something—working, in the current British situation—despite government regulations against foreigners. The control of foreigners ultimately justifies the control of citizens. Even those who support some control of immigration should realize that. If you are an American citizen and theoretically non-deportable, how can you prove it without official ID papers (and perhaps after spending a couple of hours or days in an immigration jail)?

The proliferation of government services is the second broad reason requiring beneficiaries to be tagged (I won’t say “like cattle” since it is already a cliché). Even one who supports these services should realize that tagging is one of their costs. This cost in terms of liberty and dignity increases if a unique, encompassing tag is required for all government services. The reason, of course, is again that it makes surveillance and coercion less expensive for the government.

My previous post explains that, in 1940, Philippe Pétain’s collaborationist government in non-occupied France used the excuse of citizens’ convenience to impose an official ID card on them, two decades after imposing one on foreigners. On his digital ID project, the British prime minister said that “it will also offer ordinary citizens countless benefits, like being able to prove your identity to access key services swiftly—rather than hunting around for an old utility bill.” It will also, he said, “help the Home Office take action on employers who are hiring illegally.”

Incidentally, the example of India, which the British government invokes in support of its project, shows that a single electronic ID may not have its supposed monopolistic effectiveness if it fuels an ID obsession. For one thing, this-or-that bureau can be tempted to build upon the “unique ID” by creating its own digital ID for a sub-clientele. (“India Is Obsessed With Giving Its People ‘Unique IDs,’” The Economist, May 20, 2025.)

In a free society, some tools should not be available to the state. Imperfections with liberty are better than perfection with servitude. But I fear we lost the ID-card battle—”we,” those who realize the need to constrain the state.

In the early 2000s, I spent some time in England. I was heartened to discover that one did not need to show any official ID in daily life—for example, when subscribing to a film rental service. A driver’s license was, of course, required to drive a car, which reminds us that this was how “real ID” has become accepted by most Americans. Two decades ago, the Labour government of Tony Blair was already planning a compulsory ID card, but, contrary to what a simple theory of Leviathan suggests, the project was killed by a coalition of the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats after the 2010 election. Yet, nothing in the theory says that Leviathan (as an institution) will only try once to get the new powers it wants.

******************************

This EconLog post (my 797th) will be my last. I want to thank Liberty Fund for the opportunity to be part of the blog. I am also grateful to my readers, whose comments have often influenced my thinking, even if perhaps it did not always show! You are most welcome to follow and discuss my posts at my Substack newsletter, Individual Liberty. On my barebones website, I maintain a list of (and links to) my other articles, including those at Regulation, where I am a contributing writer.

Featured image is from ID Card by Gareth Harper under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

(24 COMMENTS)RSS Error: A feed could not be found at `https://www.irishtimes.com/rss/activecampaign-business-today-digest-more-from-business-1.3180340`; the status code is `404` and content-type is `text/html; charset=utf-8`